John R. Kelso’s Civil Wars:

A Graphic History - 1862

10. THE MARCH TO PEA RIDGE

In a letter to his wife Susie, Kelso described the Army of the Southwest’s winter campaign of 1862 as “a chase scarce equaled on any other occasion in American history.” Led by Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, over 12,000 Federals again marched southwest toward Missouri’s southwest corner. The chase accelerated in February as the Confederates evacuated Springfield and headed for Arkansas, and the Federals hurried after them. On most evenings, the head of Union army would skirmish with the Confederate tail, sometimes for a few minutes and sometimes for an hour or more, and then the rebels would withdraw further south and the Federals would occupy the camp their enemy had just abandoned. “After a long march all day,” Kelso told Susie, the men “would be so weary that many seemed scarce able to drag themselves along; but, when the roar of cannons was heard in advance, all would spring forward, at double quick, seeming strong as ever, while loud cheers echoed along our ranks. At such times, we plunged through creeks, tore through bush, all regardless of consequences, our only feeling being one of wild gladness at the prospect of getting a fight.”

After weeks of skirmishing and hundreds of miles of marching through mud and ice, the armies clashed at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7-8, 1862-- the largest Civil War battle fought west of the Mississippi River. The Union Army of the Southwest beat a larger Confederate force. The Federals suffered over 1,300 casualties and the Confederates about 2,000. It was strategic turning point in Federal efforts to control Trans-Mississippi region. Still, the bloody and brutal Civil War would grind on in Missouri—as in many other places—for another three years.

11. THE BATTLE OF NEOSHO

May 1862. Kelso had become a lieutenant in the Missouri State Militia Cavalry. When his regiment was sent to Neosho, the troops were still green. Their bumbling colonel, John M. Richardson, pitched the camp in a vulnerable spot, expecting the small bands of prowling rebels and allied Indians to stay far away. Instead, the enemy attacked on the morning of May 31.

Hearing war whoops and gunshots and then seeing “citizens scampering in all directions,” Kelso and some other officers began to race to their men. As they were “streaking it down an open street, the bullets began to whistle uncomfortably thick and close about our ears.” One soldier was hit. Others dove for cover. Ahead, the cavalrymen struggled to form a line. Kelso darted behind them as the rebels fired another volley. “The terrific crash of bullets among the foliage around us seemed sufficient to wither every-thing before it. The roar of the guns, the fearful yelling of the Indians, the rearing and the plunging of our frightened horses, the cries of our wounded as they fell to the ground, made a scene dreadful almost beyond description.”

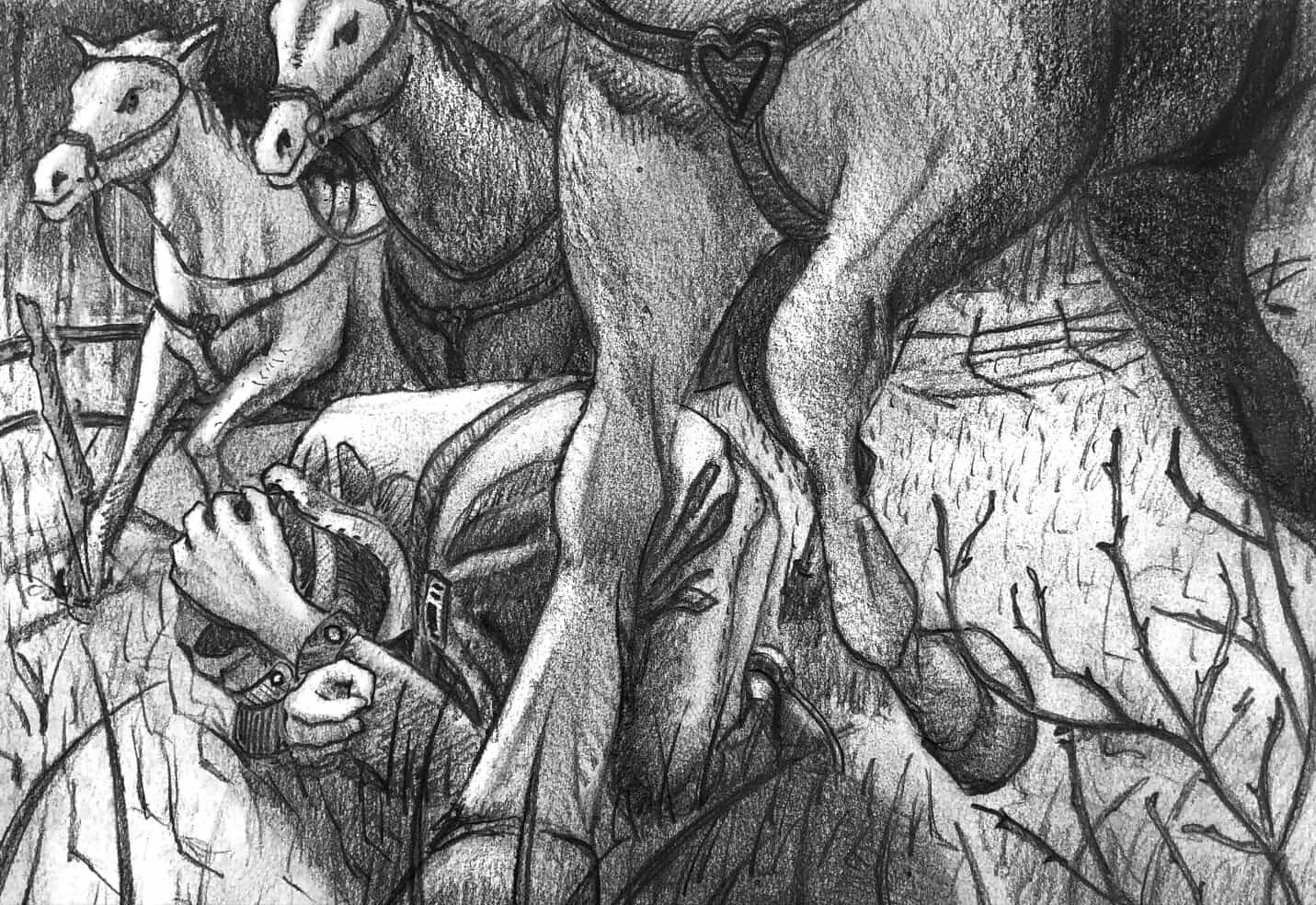

Another rebel volley. The colonel and his horse crumpled to the ground. The line broke, and the men turned to flee, galloping back toward Kelso, crowding toward a corral gate behind him. “In a compact mass they ran over me, knocked me down . . . There was no room for me between the closely packed bodies of the horses. . . . By a strange kind of instinct, the horses, though they could not see me, avoided stepping directly upon me” though they “bruised the back of my head with the corks of their shoes.”

When they had all passed over him, Kelso arose, covered in dust--coughing, spitting, wiping his eyes. Needing to get his gun and his horse, he dashed to his tent, the bullets screaming past him. He managed to mount Hawk Eye under heavy fire, spur his horse to leap two high fences, and make his escape.

12. THE MEDLOCK RAID

In the summer and fall of 1862, the MSM Cavalry, posted at small bases, would ride out on patrols to battle the numerous small bands of rebel guerrillas that were stealing or destroying property, ambushing soldiers, and murdering loyal civilians. The cavalry also engaged the larger bodies of irregulars operating quasi-independently from the Confederate command. After the debacle at Neosho, Kelso’s regiment became a potent counter-insurgency force in southwest Missouri. And Kelso himself emerged as a noted guerrilla hunter.

He was the hero of a raid on “a large band of rebel thieves and cut-throats led by two Medlock brothers.” He had not intended to charge one of their hideouts alone, but his men had fallen behind, and Kelso, running through dense hazel bushes suddenly burst right into the yard in front of Captain Medlock’s house.

About a dozen men had been sleeping around a campfire. The Captain “was just taking a seat outside of the house near the door to put on a pair of shoes.” The men looked up to see Kelso bound out of the bushes. They gaped at him in astonishment.

Kelso rushed up and, quick as a flash, decided to yell, “Close in, boys, we’ll get every one of them!” Imagining that Kelso’s troops were right behind him in the hazel bushes, men in the yard bounded up from their blankets. Some of them tried to grab their boots, pants, and guns as they scattered. Captain Medlock, too, a large, heavy man, started to run. But as he reached the end of the house, he stopped and realized that only a single man was charging. Medlock turned back toward the doorway and rushed to get his gun. Kelso was right behind him. Medlock lunged for his gun at the far side of the room. Just as his hand touched the gun, Kelso stuck his revolver into Medlock’s back and fired. “He fell like an ox, his fall shaking the whole house.”

13. DEATH WALTZ

The Federals learned where four “cut-throats” led by Captain Wallace Finney took their meals. Creeping up to the house through a cornfield to scout the situation while the rest of his men waited at the edge of the forest, Kelso was spotted by some women in the yard, who started screaming. Fearing that the four rebels, inside eating breakfast, would be able to dash out to their horses and escape before the other men could come up, Kelso charged the house on his own. Sprinting forward with revolvers in each hand, he started shooting when the four emerged from the doorway. One rebel, wounded, staggered into the nearby brush thicket. Two others mounted and were escaping. The fourth—Finney—was slower unhitching his horse. Kelso was almost upon him. The bushwhacker mounted and began drawing his revolver. The guns in Kelso’s hands were empty. He had two more on him, but could not draw in time. He lunged for Finney’s arm and pulled him off his horse.

Kelso landed on top of Finney and at first tried to pin him to the ground. But the two mounted rebels were close by, and they leveled their revolvers at Kelso. So he quickly pulled Finney to his feet and tried to use the bushwhacker’s body as a shield. Finney had the same idea. “Throwing his arms about me, he whirled me around so that his comrades could shoot me with less danger to himself. With all my power, I whirled him so that, if they fired, they would hit him. And thus in this violent waltz of death we whirled.”

Gunshots, close by, just in time, made the two mounted bushwhackers turn away from the death waltz and spur their horses. It was only then that Kelso was able to “fix my waltzing partner.” Finney delivered “several staggering blows” to Kelso’s head. Kelso drew, fired into Finney’s stomach, and hit him over the head with his empty gun. Finney finally fell. “I clapped my foot on the back of his neck and pressed his head down. I drew my last revolver and put a shot through his brain.”

14. ATTACK ON THE SALTPETER MINE

In early December 1862, Kelso and his comrades were dressed as rebels. They sat in their saddles in front of a Confederate army barracks on a bluff above the White River. They aimed to destroy a Confederate saltpeter mine, which would deliver a powerful blow to the enemy’s gunpowder production. Thirty-six men could not take the barracks by direct assault. But they had learned that a Confederate force, 2,000 strong, was approaching from the south. Pretending to be an advance rebel detachment, they might be able to capture the men in the barracks, destroy the equipment in the cave, and quickly escape across the river.

The men at lunch in the barracks left their guns behind to greet the newcomers and were quickly captured. As Capt. Burch dealt with the surly prisoners, Kelso alone descended the long flight of steps leading from the barracks to the cave entrance on the riverbank. The one soldier there made a move toward his gun, but Kelso shouted “Move and you die! Stand right still!” So the man froze. Shortly, Burch appeared and set some of the prisoners to work with axes and sledgehammers, destroying anything that might not burn.

Clouds of dust rose in the trees: the Confederates were coming. Burch and the others took the prisoners and forded the river. Kelso and one soldier stayed behind to torch the barracks. Kelso, the last to cross the river, turned to survey his destructive work. The air was still and the river placid, but flames from the blockhouse shot up a hundred feet. Billowing smoke rose far higher, reaching up toward some dark storm clouds spreading out “like a vast umbrella in all directions.” Although the spent bullets from the hundred Confederates firing from the bluff “began to patter like hail” around him, he had to pause to admire a scene “of weird and wonderful grandeur.”