John R. Kelso’s Civil Wars:

A Graphic History

Preface

“John R. Kelso’s Civil War: A Graphic History” has been adapted from the biography of Kelso by Christopher Grasso, Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy: The Civil Wars of John R. Kelso (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

The text of the Graphic History is by Grasso. The illustrations are by Robert W. Davidson (osakanart.com).

In the “Read More” link at the end of each segment, the author discusses the broader context of each episode in the biography. The illustrator comments on the artistic choices he made to turn the narrative into an arresting image.

JOHN R. KELSO

Teacher, preacher, soldier, spy; congressman, scholar, lecturer, author; Methodist, atheist, spiritualist, anarchist. John R. Kelso (1831-91) was also a strong-willed son, a passionate husband, and a loving and grieving father. At the center of his life were the thrill and the trauma of the Civil War, which challenged his notions of manhood and honor, his ideals of liberty and equality, and his beliefs about politics, religion, morality, and human nature.

He fought for the Union in Missouri, serving as an infantry private marching to large battles, a spy gathering intelligence in enemy territory, a cavalry officer fighting Confederate guerrillas, and a lone gunman taking revenge on the rebels who wronged him.

Growing up in a rough backwoods cabin, he had educated himself by firelight. A Methodist preacher, he left the church when his first marriage crumbled and his congregation turned against him. A schoolteacher, he left his schoolhouse when, in the spring of 1861, Missouri and the United States split in half.

2. BUFFALO TOWN SQUARE, SECESSION SPRING, 1861

May 7, 1861. Jubilant speakers addressed a crowd in front of the courthouse in Buffalo, Missouri. Two more states had seceded from the Union. “The Union seemed to have no friends present,” Kelso thought darkly as he heard people cheering the Confederacy.

Up until this moment, he had kept his unpopular Union sympathies to himself. But as he crossed the square, he felt compelled to take a stand. He climbed the courthouse steps and called for attention. Secession was treason, he declared to his stunned neighbors, and he would fight to the death for the United States.

At first, only shocked silence. Then a murmur. Some louder voices began denouncing him: “He’s a traitor to the South.” “He ought to be shot down like a sheep-killing dog.” As the crowd’s fury built, Kelso felt a child’s fingers clutching his hand. An eight year-old boy, one of his students, tugged him away and led him to a darkened warehouse. Four men, secret Unionists, told him to keep quiet and lay low. Kelso refused and instead asked to borrow a pistol.

3. SECESSION RALLY

A week later, secessionists marched into the crowded town square for a rally. They had a Confederate flag, a band ready to play Dixie, and men ready to fire their guns into the air. To loud cheers, a speaker cited scripture to prove that the Confederacy was God’s Holy Cause. But then Kelso leaped onto the stand, waved his hand for attention, and began to address the crowd.

He cited scripture to argue that the seceding states were instead minions of Satan, rebelling against God. He spoke not just to damn the rebels but to embolden timid Unionists and to convert the undecided. “My whole being seemed aglow with a strange inspiration. I seemed to see in great letters of flame the very words that I should speak.” He invoked George Washington, the glorious Union, and the Star-Spangled Banner. “Tears—loyal tears rolled down the rough cheeks of many a brave and honest man who came there believing himself to be a secessionist. . . . A mighty revolution was being wrought in that great assembly. A tidal wave of loyalty was rising that could not now be turned back, or resisted. When I closed, the pent up feelings of hundreds found vent in loud and hearty hurrahs for the Union and our brave old flag.” The secessionists clattered away in their wagons as the Union men cheered and led him to a darkened warehouse. Four men, secret Unionists, told him to keep quiet and lay low. Kelso refused and instead asked to borrow a pistol.

4. FIRST BATTLEFIELD

Missouri divided. Kelso helped organize a Unionist “Home Guard” militia in Dallas County. In nearby counties, secessionists organized “State Guard” militias. Federal troops from St. Louis led by Gen. Nathaniel Lyon chased State Guard troops led by secessionist Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson to the southwest corner of the state. Kelso’s men just missed joining Lyon for the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, 1861, where the Federals lost to a pro-Confederate force twice their size and Lyon and 257 other Union soldiers died. Home Guard units dissolved and Unionists fled north. Though having been a major in the militia, Kelso joined the 24th Missouri Infantry as a private to make a point about patriotism.

His first taste of battle was in October. Confederates attacked a small unit guarding the Iron Mountain Railroad Bridge 50 miles south of St. Louis. Kelso’s company rushed there at night in open train cars. When he reached the battlefield, he saw Union soldiers dead in a stone pen where they had made their last stand. “Most of them had been shot in the head as they stood on their knees firing over their low stone wall. They had fallen backward, and I shuddered as I gazed upon their ghostly upturned faces and their glassy eyes gleaming in the moonlight.” Rebel troops had bled and fallen only a dozen yards away. A few days later, the enemy returned, and Kelso and his men fired from rifle pits as the bullets flew thick over their heads.

5. A SPY IN THE RAIN

Kelso began his first solo spy mission in the fall of 1861. The Confederates held southwestern Missouri; the Federals controlled the rest of the state. After taking the train from St. Louis to the end of the line at Rolla, Kelso headed on foot to occupied Springfield, 120 miles away. On that first night, and for many after, he slept in the forest, in the cold rain, back to a tree trunk and gun at the ready. “I dare not kindle a fire. . . . That dreary night seemed like the longest I ever knew.”

Such off-the-books spy missions by soldiers on special assignment were not unusual. The U.S. Army did not have a formal spy agency. Commanders recruited men who had the skills to travel alone through hostile territory, the intelligence to know what to look for, and the inclination to take risks. They knew that for every spy who successfully penetrated the enemy’s camp there might be three or four captured and a dozen turned back at the picket lines. So the officers sent out multiple men, separately but with the same mission. Spies like Kelso traveled hundreds of miles alone, in difficult conditions and dangerous circumstances, but the built-in redundancy made them, ultimately, expendable.

Spies traveled under false pretenses and under assumed identities, in disguise as civilians or in the enemy’s uniform, and if captured they could be summarily executed. “Don’t you know,” one officer said, “that when you go out as a spy, you go, as it were, with a rope around your neck, ready for anybody to draw it tight?”

6. COVER BLOWN

At the beginning of his second spying expedition, calling himself “John Russell,” Kelso stopped at a log hut for breakfast and tried to convey his Southern sympathies. The half-dozen well-armed men at the table seemed suspicious. But he worried even more about “the woman of the house, sharper than any of the men, who seemed to read me at once.” Feeling her eyes upon him, he realized that he had made a stupid mistake. Disguised as a civilian, he had nonetheless crammed his coat pockets with hardtack, the distinctive cracker issued to Union soldiers. She glanced at his bulging pockets, then pulled her husband aside to whisper. After bolting a few mouthfuls of breakfast, Kelso excused himself and continued on his way, quickly leaving the road for the forest, dumping the hardtack, and hiding his revolvers more carefully under his coat.

As he traveled along the Arkansas border, he knew he would need to do a better job performing the “John Russell” people needed to see. He put on his best parlor manners for a Confederate officer who invited him to dinner, and then helped give pro-Confederate speeches at rebel recruiting stations. To bum some breakfast at a dilapidated cabin, he adopted the coarse manners and virulent anti-Black and anti-Yankee attitudes of the dirt-poor hunter inside. Seeking shelter at the farmhouse of a pious Southern woman, “Russell” quickly became pious and Southern too, praising the Lord for the gallant boys in gray. By the time he made it back to Federal picket lines, he was so used to shifting his identity to meet the moment that he could hardly give a straight answer when guards demanded that he identify himself.

7. REFUGEES IN A SNOWSTORM

Gen. John C. Frémont’s five divisions left St. Louis on Sept. 27, and slowly moved diagonally across the state with the promise to clear the rebels from the southwest corner once and for all. But with a series of blunders he had already lost the confidence of commanders in Washington, politicians in Missouri, and his own officers. Fearing disaster, President Lincoln removed him from command shortly after he’d reached Springfield on Nov. 3. Five days later, interim commander David Hunter, worried about being caught between two Confederate armies—one coming from the east and the other from the south—withdrew his troops. Southwestern Missouri Unionists like Kelso, however, felt that the disgraceful retreat had abandoned them to “an infuriated and relentless foe,” surrendering their homes to plunder and flame and sacrificing many civilian lives to the rebels’ vengeance. And, indeed, rebel neighbors soon burned down Kelso’s house and prevented anyone from sheltering his wife and children.

Kelso was ordered to evacuate his family and other loyal Unionists from Buffalo. A blizzard struck the refugee wagon train. Secessionists along the route refused to give them shelter. The refugees stopped at night and tried to make camp in an open field covered with small trees. They hacked down some green wood and kindled miserable fires that produced more smoke and sparks than heat. Some were already frostbitten. His wife and children tried to sleep upon a few old blankets, placed upon the snow.

He wandered the camp. At a distant fire, he tried to help hang blankets to shield from the swirling snow a young woman giving birth. He heard her utter a prayer, heard her baby’s faint cry, and then watched them both die.

He was filled with “unutterable bitterness.” The blood in his veins felt “strangely hot.” He blamed the rebels for all the suffering.

8. VOW OF VENGEANCE

On another spy mission, he returned to his hometown. At midnight, he crept from the dark forest and onto his own property. He stood upon the ashes of his home. There, in the moonlight, was his children’s playhouse; beyond was his orchard, ruined by his rebel neighbor’s sheep. Bitterly, he took off his hat, called the moon to witness, and “vowed to slay with my own hand twenty-five rebels.” Years later he would see this vow as a kind of “madness,” but he also knew that it made the story of what happened next “more wonderful than almost any fiction.”

He hid in the woods outside Buffalo and terrorized the town for nearly three weeks. Ignoring hunger, cold, exhaustion, and the danger of getting caught, he focused on revenge. He had learned the names of several of the men who had burned down his house. Most were men he knew, men he had never harmed or offended. He would meet them, as he put it, to “transact some very important business.” Fear “spread like the wind.” Rumors reverberated through the town. “Like an evil spirit that knew no rest, I appeared and disappeared leaving them all wondering whence I came and whither I went.” He had begun his quest for revenge.

9. CAUGHT BY THE REBELS

The Confederate cavalry caught him, and recognized him as a spy. He admitted it, knew they would hang him for it, and told them he planned to die like a man. But as they built a gallows from fence rails, he tried to ingratiate himself with them by telling “ludicrous anecdotes” that kept them laughing. He overheard some of the men arguing about his fate. One of them said that it was “a damned pity for so brave a man to be strung up like a damned dog.” A sympathetic guard wordlessly signaled to Kelso that he would help him escape. The soldier glanced at the brush thicket behind him.

The minutes ticked by. The gallows were ready. “My heart seemed to cease beating.” Then a soldier called his comrade a liar, and the man responded by throwing a punch. Kelso knew that was the signal—a distraction staged for his sake. He darted toward the brush. The friendly guard then happened to stumble out of his way and into the path of two pursuers. Kelso plunged into the thicket and ran for his life. Four guns fired behind him. Bugles sounded and soldiers mounted their horses, but the escaping prisoner could only be followed through the dense thicket on foot.

Kelso ran, plowing through the briars and brush, and then had to force himself to stop running, for it was better to stay in the thicket than venture out onto the open ground beyond it. He hid in the snow beneath the bushes, hat gone, clothes “torn to tatters,” chest heaving, blood and sweat trickling over dozens of scratches, and feeling “a wild joy hard to describe.”

10. THE MARCH TO PEA RIDGE

In a letter to his wife Susie, Kelso described the Army of the Southwest’s winter campaign of 1862 as “a chase scarce equaled on any other occasion in American history.” Led by Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, over 12,000 Federals again marched southwest toward Missouri’s southwest corner. The chase accelerated in February as the Confederates evacuated Springfield and headed for Arkansas, and the Federals hurried after them. On most evenings, the head of Union army would skirmish with the Confederate tail, sometimes for a few minutes and sometimes for an hour or more, and then the rebels would withdraw further south and the Federals would occupy the camp their enemy had just abandoned. “After a long march all day,” Kelso told Susie, the men “would be so weary that many seemed scarce able to drag themselves along; but, when the roar of cannons was heard in advance, all would spring forward, at double quick, seeming strong as ever, while loud cheers echoed along our ranks. At such times, we plunged through creeks, tore through bush, all regardless of consequences, our only feeling being one of wild gladness at the prospect of getting a fight.”

10. THE MARCH TO PEA RIDGE

In a letter to his wife Susie, Kelso described the Army of the Southwest’s winter campaign of 1862 as “a chase scarce equaled on any other occasion in American history.” Led by Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, over 12,000 Federals again marched southwest toward Missouri’s southwest corner. The chase accelerated in February as the Confederates evacuated Springfield and headed for Arkansas, and the Federals hurried after them. On most evenings, the head of Union army would skirmish with the Confederate tail, sometimes for a few minutes and sometimes for an hour or more, and then the rebels would withdraw further south and the Federals would occupy the camp their enemy had just abandoned. “After a long march all day,” Kelso told Susie, the men “would be so weary that many seemed scarce able to drag themselves along; but, when the roar of cannons was heard in advance, all would spring forward, at double quick, seeming strong as ever, while loud cheers echoed along our ranks. At such times, we plunged through creeks, tore through bush, all regardless of consequences, our only feeling being one of wild gladness at the prospect of getting a fight.”

After weeks of skirmishing and hundreds of miles of marching through mud and ice, the armies clashed at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7-8, 1862-- the largest Civil War battle fought west of the Mississippi River. The Union Army of the Southwest beat a larger Confederate force. The Federals suffered over 1,300 casualties and the Confederates about 2,000. It was strategic turning point in Federal efforts to control Trans-Mississippi region. Still, the bloody and brutal Civil War would grind on in Missouri—as in many other places—for another three years.

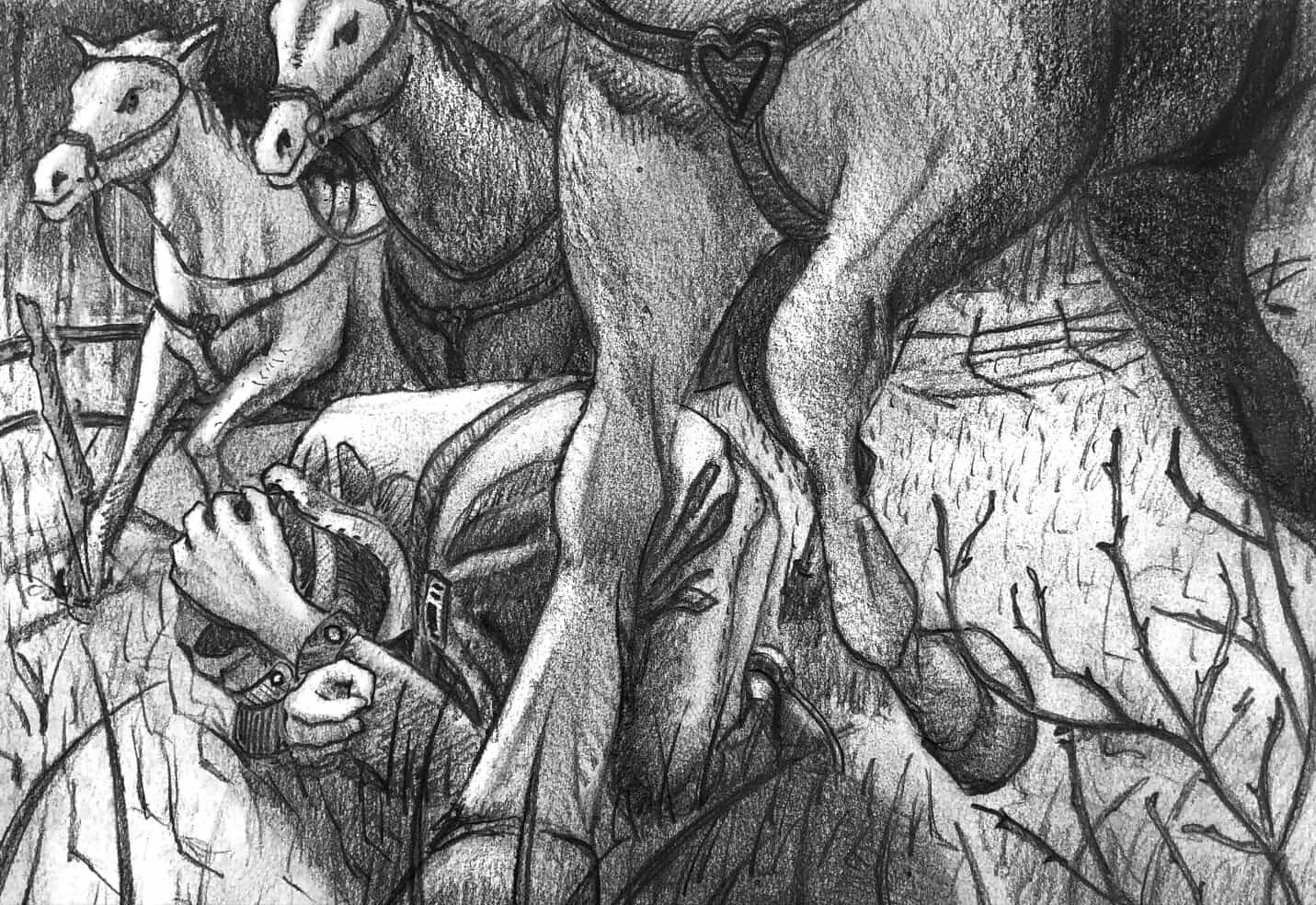

11. THE BATTLE OF NEOSHO

May 1862. Kelso had become a lieutenant in the Missouri State Militia Cavalry. When his regiment was sent to Neosho, the troops were still green. Their bumbling colonel, John M. Richardson, pitched the camp in a vulnerable spot, expecting the small bands of prowling rebels and allied Indians to stay far away. Instead, the enemy attacked on the morning of May 31.

Hearing war whoops and gunshots and then seeing “citizens scampering in all directions,” Kelso and some other officers began to race to their men. As they were “streaking it down an open street, the bullets began to whistle uncomfortably thick and close about our ears.” One soldier was hit. Others dove for cover. Ahead, the cavalrymen struggled to form a line. Kelso darted behind them as the rebels fired another volley. “The terrific crash of bullets among the foliage around us seemed sufficient to wither every-thing before it. The roar of the guns, the fearful yelling of the Indians, the rearing and the plunging of our frightened horses, the cries of our wounded as they fell to the ground, made a scene dreadful almost beyond description.”

Another rebel volley. The colonel and his horse crumpled to the ground. The line broke, and the men turned to flee, galloping back toward Kelso, crowding toward a corral gate behind him. “In a compact mass they ran over me, knocked me down . . . There was no room for me between the closely packed bodies of the horses. . . . By a strange kind of instinct, the horses, though they could not see me, avoided stepping directly upon me” though they “bruised the back of my head with the corks of their shoes.”

When they had all passed over him, Kelso arose, covered in dust--coughing, spitting, wiping his eyes. Needing to get his gun and his horse, he dashed to his tent, the bullets screaming past him. He managed to mount Hawk Eye under heavy fire, spur his horse to leap two high fences, and make his escape.

12. THE MEDLOCK RAID

In the summer and fall of 1862, the MSM Cavalry, posted at small bases, would ride out on patrols to battle the numerous small bands of rebel guerrillas that were stealing or destroying property, ambushing soldiers, and murdering loyal civilians. The cavalry also engaged the larger bodies of irregulars operating quasi-independently from the Confederate command. After the debacle at Neosho, Kelso’s regiment became a potent counter-insurgency force in southwest Missouri. And Kelso himself emerged as a noted guerrilla hunter.

He was the hero of a raid on “a large band of rebel thieves and cut-throats led by two Medlock brothers.” He had not intended to charge one of their hideouts alone, but his men had fallen behind, and Kelso, running through dense hazel bushes suddenly burst right into the yard in front of Captain Medlock’s house.

About a dozen men had been sleeping around a campfire. The Captain “was just taking a seat outside of the house near the door to put on a pair of shoes.” The men looked up to see Kelso bound out of the bushes. They gaped at him in astonishment.

Kelso rushed up and, quick as a flash, decided to yell, “Close in, boys, we’ll get every one of them!” Imagining that Kelso’s troops were right behind him in the hazel bushes, men in the yard bounded up from their blankets. Some of them tried to grab their boots, pants, and guns as they scattered. Captain Medlock, too, a large, heavy man, started to run. But as he reached the end of the house, he stopped and realized that only a single man was charging. Medlock turned back toward the doorway and rushed to get his gun. Kelso was right behind him. Medlock lunged for his gun at the far side of the room. Just as his hand touched the gun, Kelso stuck his revolver into Medlock’s back and fired. “He fell like an ox, his fall shaking the whole house.”

13. DEATH WALTZ

The Federals learned where four “cut-throats” led by Captain Wallace Finney took their meals. Creeping up to the house through a cornfield to scout the situation while the rest of his men waited at the edge of the forest, Kelso was spotted by some women in the yard, who started screaming. Fearing that the four rebels, inside eating breakfast, would be able to dash out to their horses and escape before the other men could come up, Kelso charged the house on his own. Sprinting forward with revolvers in each hand, he started shooting when the four emerged from the doorway. One rebel, wounded, staggered into the nearby brush thicket. Two others mounted and were escaping. The fourth—Finney—was slower unhitching his horse. Kelso was almost upon him. The bushwhacker mounted and began drawing his revolver. The guns in Kelso’s hands were empty. He had two more on him, but could not draw in time. He lunged for Finney’s arm and pulled him off his horse.

Kelso landed on top of Finney and at first tried to pin him to the ground. But the two mounted rebels were close by, and they leveled their revolvers at Kelso. So he quickly pulled Finney to his feet and tried to use the bushwhacker’s body as a shield. Finney had the same idea. “Throwing his arms about me, he whirled me around so that his comrades could shoot me with less danger to himself. With all my power, I whirled him so that, if they fired, they would hit him. And thus in this violent waltz of death we whirled.”

Gunshots, close by, just in time, made the two mounted bushwhackers turn away from the death waltz and spur their horses. It was only then that Kelso was able to “fix my waltzing partner.” Finney delivered “several staggering blows” to Kelso’s head. Kelso drew, fired into Finney’s stomach, and hit him over the head with his empty gun. Finney finally fell. “I clapped my foot on the back of his neck and pressed his head down. I drew my last revolver and put a shot through his brain.”

14. ATTACK ON THE SALTPETER MINE

In early December 1862, Kelso and his comrades were dressed as rebels. They sat in their saddles in front of a Confederate army barracks on a bluff above the White River. They aimed to destroy a Confederate saltpeter mine, which would deliver a powerful blow to the enemy’s gunpowder production. Thirty-six men could not take the barracks by direct assault. But they had learned that a Confederate force, 2,000 strong, was approaching from the south. Pretending to be an advance rebel detachment, they might be able to capture the men in the barracks, destroy the equipment in the cave, and quickly escape across the river.

The men at lunch in the barracks left their guns behind to greet the newcomers and were quickly captured. As Capt. Burch dealt with the surly prisoners, Kelso alone descended the long flight of steps leading from the barracks to the cave entrance on the riverbank. The one soldier there made a move toward his gun, but Kelso shouted “Move and you die! Stand right still!” So the man froze. Shortly, Burch appeared and set some of the prisoners to work with axes and sledgehammers, destroying anything that might not burn.

Clouds of dust rose in the trees: the Confederates were coming. Burch and the others took the prisoners and forded the river. Kelso and one soldier stayed behind to torch the barracks. Kelso, the last to cross the river, turned to survey his destructive work. The air was still and the river placid, but flames from the blockhouse shot up a hundred feet. Billowing smoke rose far higher, reaching up toward some dark storm clouds spreading out “like a vast umbrella in all directions.” Although the spent bullets from the hundred Confederates firing from the bluff “began to patter like hail” around him, he had to pause to admire a scene “of weird and wonderful grandeur.”

15. THE BATTLE OF SPRINGFIELD

Jan. 8, 1863. Kelso’s detachment had been racing up from northern Arkansas to Springfield, an invading force of several thousand Confederates commanded by Gen. John S. Marmaduke right behind them. Springfield was a crucial military depot, but it was weakly defended: including green militiamen and hospitalized soldiers, it had about 2,300 men. The town’s defenders hurriedly pierced walls for musket fire, stocked the two forts with provisions, and refurbished some old cannons. Civilians hid their money and headed for their cellars. A newspaper reporter summed up the general feeling: we won’t give up the town without a fight, “but we shall probably be whipped.”

The battle began at 10:00 a.m. as rebel artillery opened fire. Cavalry—including Kelso’s squad on the eastern flank—began skirmishing, and rebel infantry began moving into the southern part of town. The attackers advanced by crawling “like Indians,” the reporter said, “from one stump to another, sheltering themselves as much as possible, but keeping up the deadly fire.” As the rebels pushed closer to the town center, a dozen men died in a few moments in a fight over a cannon. In the east, Kelso and his men were nearly cut off when a larger rebel cavalry swept in. By nightfall, the Confederates occupied the lower third of the town.

The main fighting had stopped, but the artillery shelling continued. Sent out as a scout, Kelso crept onto the dark battlefield among the dead and wounded as shells continued to pass overhead. When a Confederate ambulance wagon came by, he held his breath, face in the cold dirt, pretending to be dead.

Then the shelling stopped and Marmaduke’s forces withdrew. In the grim bookkeeping that followed, Union commanders reported 14 killed and 146 wounded, though another dozen would die from their wounds in the days that followed; Marmaduke reported 19 killed and 105 wounded, though a Springfield physician knew of 80 Confederate burials. Springfield remained in Union hands.

16. HERO OF THE SOUTH WEST

Unionists called Kelso “The Hero of the South West.” Stories about him spread. He was part of expeditions of as many as 200 men against enemy bases in northern Arkansas and helped lead strike forces of 60 riders against guerrilla hideouts. With squads of 10 men, he attacked small outlaw camps. Sometimes he would charge a bushwhacker cabin by himself. Unionists celebrated his daring and courage. Secessionists called him a ferocious “rebel-killer” who “butchered his victims” with an “unforgiving heart.”

Once he went out alone into the Ozark Mountains, disguised as a bushwhacker. He joined a rebel camp, but most of the bandits left him behind with two who did not trust him—they “never took their hands off their guns for a moment.” Kelso, chatting with them affably, pretended to have a splinter in his finger and held out his hand for them to see. As they leaned forward, “each let the butt of his gun drop to the ground.” In a flash, Kelso “seized the gun of the nearest bandit” with one hand while drawing his revolver with the other and shooting both rebels.

Another time, Kelso and his men surrounded a house. He “saw three bandits within, and keeping his eyes on them and his hands on his shotgun in the position of ‘ready,’ crossed the fence and started for the door.” As he did so, “a big dog came snarling and growling at him and seized him by the calf of the leg. Not in the least disconcerted by this unexpected attack of the dog, he stopped, and keeping his eyes on the bandits took with his right hand his revolver from the scabbard, and feeling for the dog’s neck shot the beast dead. He proceeded as if nothing had happened.” Seeing this, the bandits fled without firing a shot.

17. WOUNDED WARRIOR

Kelso became known for riding his charmed claybank horse, Hawk Eye, and for carrying an extra-large shotgun. Yet when his luck finally evaporated in the late summer of 1863, it was a shotgun blast and an accident with Hawk Eye that gave him injuries that would trouble him the rest of his life.

Kelso and his men were galloping after three bushwhackers. As a rebel turned to fire his shotgun, Kelso instinctively slid to the right on his saddle and was hit “slantingly.” He “felt the shots, like heavy hot irons, tearing through my flesh on my left breast and in my left hand.”

Only later, after the bushwhackers and one of Kelso’s own men had been killed, could he assess his injuries. He had fifteen wounds. A bullet lodged in one of his fingers would leave his left hand partially disabled. The shots in his chest “looked like a cluster of ugly blue bumps,” causing inflammation and pain. So he took his pocket-knife and cut them out. But he missed one, he would come to think. Lodged beneath his sternum, it would, he believed, fester for years and eventually kill him.

A month later, Kelso was galloping in pursuit of another band of bushwhackers. His picket rope fell to the ground and got tangled in Hawk Eye’s legs. Horse and rider did a somersault. “The great weight of the horse . . . crushed me to the earth, rupturing me badly in the right groin, partially dislocating my hips, and seriously injuring them in the joints. My left shoulder was also severely injured, my head and left ankle severely bruised.” These injuries, too, would never fully heal.

But he refused to be kept from the field. He had to be carried to his horse and placed on his saddle each morning, and then carried from his horse and placed on his blanket each evening.

18. THE DEPARTED

Kelso had written a short note to his wife Susie in late February 1864, “worn out from a long and toilsome scout,” his hand “so unsteady” that he could barely write. There were many more long and toilsome scouts through the first half of 1864. He had been promoted to captain and had launched his political career. But as the war dragged on, good officers, well-intentioned and able, could make mistakes, and men died. Brave soldiers, doing their duty, could be just a step wrong or a second slow, and men died. In August, a year to the day after he had been seriously wounded, he was still fighting in battles “where the bullets flew thick as hail” and seeing “several of my brave boys fall mangled and bleeding around me.” He mourned the dead and was weary of mourning.

Exploring the hills in northern Arkansas, Kelso and his men came across the trail taken by “a considerable party of Federals” that had been ambushed and “cut to pieces” a few months before. Kelso found the body of a soldier. “He sat with his back against a tree, his right elbow resting upon his right knee, and his right cheek resting upon his right hand. He had evidently crept to this place mortally wounded, and had died sitting in this position.” He still wore his uniform, “but his garments hung very loosely upon him, for his flesh was now all gone except for the cartilage that held the bones together. In the bones of his left hand which rested by his side he clutched a faded photograph. It was that of a beautiful woman, with [a] happy smiling face.” He slipped the photograph back into the soldier’s hand “and left him as I found him.”

19. THE CHEROKEE SPIKES

The “Cherokee Spikes,” a brutal but elusive band of over a hundred rebel guerrillas led by Col. Thomas R. Livingston, spotted Kelso’s twenty-man scouting party. Kelso’s men could turn and run for their lives, but across the open prairie only the few on fast horses would escape. Or they could retreat to a small log house they had just passed and try to make a stand. Kelso ordered the men to the house. One, wide-eyed with fear and not wanting to reenact the Alamo, spurred his horse and deserted them.

The men occupied the house and made portholes for their rifles. Pale but determined, they laid out their cartridges and caps and looked out to see the Spikes about 300 yards away on the top of the prairie ridge, the sunlight gleaming from their weapons. One of Kelso’s young soldiers started to panic. “We’ll all be murdered! Let’s get out and leave while we can!” Joel Hood sprang toward the boy and put a cocked revolver to his ear. “Another scream and you die,” Hood said. “Yes,” Kelso added, “kill him instantly if he opens his mouth again.” As the boy sank down to the floor with a whimper, Kelso hoped that he and Hood had stamped out the panic before it could spread to the others. The only sound they heard was their own breathing.

With a great yell from the enemy, a storm of bullets slammed into the house, a few penetrating the portholes and whistling past their heads to strike the opposite wall. Aim carefully, Kelso told his men. Each of us can take out four before they reach the house. Livingston will decide to leave us alone.

But the Spikes stopped firing. Why? Kelso and his men peered out to see another, larger body of horsemen thundering over the ridge. It was Major Thomas Houts and the Federal cavalry to the rescue. The enemy galloped away. “Well, Lieutenant,” Houts said upon greeting Kelso, “we came up in time to get you out of a very tight place.” “On the contrary,” Kelso replied, “you came up just in time to rob me of a glorious victory.”

20. AMBUSH

In the late summer of 1864, an expedition of 175 Federals tracked a large rebel force through “an everlasting jungle of brush and weeds.” Up ahead, a six-man scouting party stopped at a horseshoe bend in a creek to let their horses drink. “Instantly the whole semicircle flashed into a blaze, and every man and every horse of [the] heroic little band was riddled with bullets.”

Kelso rushed forward to help the wounded. The worst off was Cpl. “Caz” Thomas. Caz pointed to a wound and asked Kelso if it would kill him, and Kelso had to tell him the truth. A few minutes later, Kelso, weeping, helped carry his dead body away in a blanket.

As the sun set, the MSM began their retreat. Kelso stayed behind to see if the rebels sent any pursuit. “The ground was covered with blood [from] wounded men and wounded horses,” he remembered. “Bloody boots that had been cut from broken legs lay scattered around.” With twilight, the silent forest began to darken. “Several horses were standing there slowly bleeding to death. They stood in great puddles of blood. I went to them, and patted their necks. They looked pleased and grateful. They looked around at their bleeding wounds, and then pleadingly in my face, begging in their poor dumb way for the help which they expected at my hands but which I was not able to give them.” Kelso turned away and started to follow his men. “The poor creatures, seeing that I, their last friend, was deserting them, began to neigh piteously, and to hobble along after me, giving me looks of reproach almost human in their expressiveness. One of them dragged, tumbling along in the dirt, a hind foot that had been entirely shot from the leg except a small strip of skin.” Kelso hurried away, trying not to look back.

21. ELECTIONEERING WITH A SHOTGUN

Admiring soldiers and grateful civilians encouraged Kelso to run for Congress in 1864. But he could only deliver a few speeches before he was sent back out into the field. “My electioneering, therefore,” he wrote, “had to be principally done in the brush, with my big shot-gun, shooting bush-whackers.”

On September 20, 1864, Confederate Gen. Sterling Price and his Army of Missouri moved across the Arkansas line into the southeast. This was no mere raid of a few thousand men. Price was leading more than 12,000 soldiers; he intended to conquer St. Louis and Jefferson City and place the entire state under Confederate rule.

Price marched north and fought at Fort Davidson on September 27. But he turned west before Saint Louis, thinking that city too well-defended, and decided against attacking Jefferson City, too. On October 23 a little south of Kansas City, the Federals routed the Confederates, and Price’s beaten and bedraggled army fled south. With two Federal divisions in pursuit, the rebels swept down along the Kansas border and toward Missouri’s southwest corner. They bore down upon the few hundred militiamen stationed at Newtonia.

Kelso and another scout, Lt. Robert H. Christian, known as “Old Grisly,” were the last two Federal soldiers in Newtonia as Price’s army began flooding into town. Kelso, on a broken-down old horse, waited anxiously for Christian, who was about eighty yards behind. The rebels saw Old Grisly and charged. Realizing that he had lost the opportunity to escape on his exhausted horse, Kelso planned to leap onto Christian’s when the lieutenant rode by. But Old Grisly stopped, turned toward the rebels, and began firing. “The rebels rushed right on, closing upon him as they came. The bullets that missed him, whistled past me.” He saw Christian fall, and learned later that the rebels “scalped Christian’s head and also his chin, which was covered with a long grisly beard.”

Kelso tossed his army hat away and hoped the rebels would mistake him for a bushwhacker. If not, he planned to open fire with both barrels of his big shotgun and then empty his revolvers at the enemy swarming around him. He also thought, “What a strange place this is for a candidate for Congress to be in so near the day of election!”

The rebels did take him for bushwhacker and rode right past him. He managed to make his way back to his own men. A few days later, he won his seat in Congress.

22. THE FINAL SHOT

On March 3, 1865, Ulysses Grant planned the final push to break Robert E. Lee’s defense of Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Jefferson Davis still hoped for divine deliverance. Abraham Lincoln, preparing for his second inauguration the next day, also wrote to Grant, telling him how to handle the enemy’s surrender.

In northwest Arkansas on March 3, a woman was angry. She had supported the Southern cause, but the prospect of defeat was not what infuriated her. Some armed Southern men had ridden up to her farm, grabbed all the bacon she had put up after slaughtering her hogs, and made off with all her seed corn for the coming spring planting. So when some Federal cavalrymen rode by not long afterward, she told them what had happened and pointed the direction the guerrillas had taken.

Up a long winding trail, through a ravine, and into some wooded hills, a man sat against a tree, cutting slices of the woman’s bacon. His horse, hitched in front of him, chomped on the seed corn. Suddenly a shotgun blast sprayed the dirt by his boots. Springing to his feet, he lunged to his horse for his gun. The shotgun fired again. One shot went through his head, and he died as he hit the ground.

As Kelso walked from the woods, he tore a piece of paper from his notebook, wrote a note and pinned it to the corpse’s coat. This was a practice the bushwhackers themselves had started. Kelso’s signed note read: “I hereby send my kindest compliments to the friends of this bush-whacker and inform them that he makes twenty-six rebels in all that have fallen by my hand. I had vowed to kill twenty-five. I have more than fulfilled my vow. I am content.” On his last scout, it was the last shot fired and the last kill by Congressman-elect Kelso in the Civil War.

EPILOGUE AS PROLOGUE

Teacher, preacher, soldier, spy; congressman, scholar, lecturer, author; Methodist, atheist, spiritualist, anarchist. John R. Kelso was many things. The Civil War was at the center of his life. Throughout his life, too, he fought private wars—not only against former friends and alienated family members, rebellious students and disaffected church congregations, political opponents and religious critics, but also against the warring impulses in his own complex character. The fuller story of his “checkered career,” moreover, offers a unique vantage upon dimensions of nineteenth-century American culture that in the twenty-first are usually treated separately: religious revivalism and political anarchism; sex, divorce, and Civil War battles; freethinking and the Wild West.

His supporters and admirers elected him to Congress for more than just his reputation as a courageous fighter. He was also known as a learned man—always pacing about camp with a book in his hands—and as a persuasive public speaker. In the House, he was a Republican pushing the Radical agenda for Reconstruction, and he was one of the first to call for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.

After his Congressional term, Kelso returned to Missouri and school teaching, but his life’s path turned sharply again, this time because of the deaths of two of his sons and the failure of his second marriage. Devastated, Kelso moved to California. He became involved in the civic life of Modesto, a railroad boomtown built on wheat, controlled by saloon owners, and occasionally policed by masked vigilantes. In the 1870s, too, he would continue to pursue the studies that led him from Christianity to atheism, delivering the lectures that would constitute the five books he published in the next decade. He also became an outspoken critic of conventional attitudes about sex and marriage, and a promoter of spiritualism.

In Kelso’s final years, his political radicalism intensified. In 1885 he moved to Longmont, Colorado. He declared himself to be an anarchist at a Colorado rally in 1889 and tried to explain what he meant in his final book, Government Analyzed (1892). In that book he also reinterpreted the Civil War, reflecting upon the misguided patriotic “blindness” that had caused him to slaughter his fellow men. Nearly done writing his chapter on “War,” at the end of a discussion of the American Civil War and slavery, and in the middle of a sentence, John R. Kelso, in early January 1891, suffering, he thought, from the lingering effects of an old war wound, put down his pen. He died on January 26.

In the twentieth century, Kelso was quickly forgotten. But the obscure publications and voluminous manuscript writings he left behind tell a remarkable story. In it, Kelso’s marriage and family life cannot be seen as peripheral to his experience as a guerrilla fighter. He had two ambitions linking his public and private lives. He had long wanted a loving companion, a soul-mate by the fireside, and he dreamed of making some grand mark upon history. His wife at home with the children could be the emotional bedrock supporting his military endeavors. When that failed, he turned instead to look first to the approval of his commanding officers and then to the admiration of the men who served under him. Through it all, a nineteenth-century ideal of manhood linked the many dimensions of Kelso’s life—as husband and father as well as teacher and preacher or soldier and politician.

From the log cabins of backwoods Ohio, to the bloody battlefields of Civil War Missouri, to the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., during Reconstruction, to the new frontiers in California and Colorado; from conventional notions of marriage to an apparent endorsement of free love and of Mormon polygamy; from evangelicalism to atheism and spiritualism; from patriotic military and government service to an anarchistic critique of American corruption: the fuller story of Kelso’s life not only further illuminates his complicated character but also the broader nineteenth-century American landscape through which he moved and found his way.

This is the endnote.

This is the endnote. This one is a little longer. It may wrap to several lines. There was a lot to say about this particular illustration.

This is another endnote.