Kelso and Anarchism

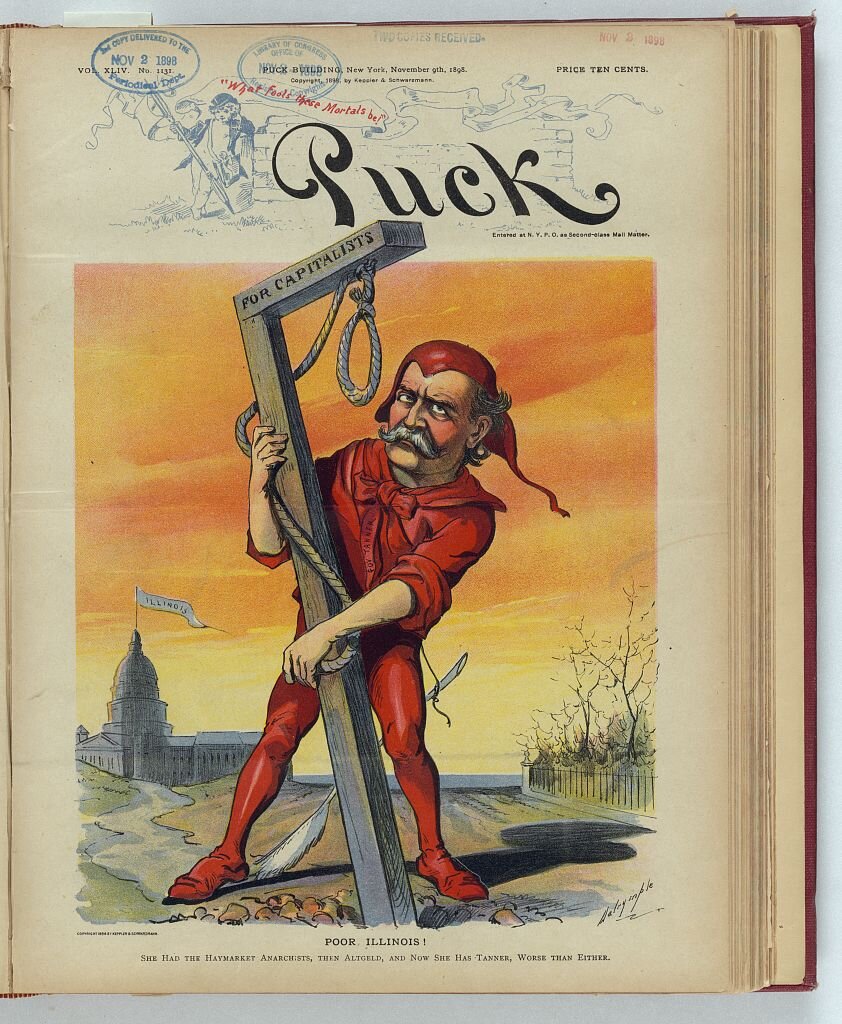

Louis Dalrymple, “Poor Illinois!”1898, Library of Congress. Print shows Illinois governor John R. Tanner.

[Adapted from Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy: The Civil Wars of John R. Kelso (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 393-402.

In early May 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, workers rallied for an eight-hour workday and to protest a police shooting that had killed a reported six strikers the day before. As policemen tried to disperse the crowd, someone threw a bomb, killing one officer and wounding others. The police opened fire, the workers fired back, and before it was over four more people in the crowd and six more policemen were mortally wounded and 130 people were injured. Eight anarchists who had organized the labor protest were arrested and put on trial in the summer of 1886. All were convicted, seven of them condemned to death. Two had their sentences commuted to life in prison, one committed suicide, and the remaining four were hanged on November 11, 1887. Kelso was among those in an international chorus who condemned the result as an outrageous miscarriage of justice. Lacking a bomb thrower and any real evidence of a conspiracy, the critics charged, a biased judge and jury condemned men for their radical ideas for labor reform.[1]

Haymarket Square, Chicago [c. 1893], Library of Congress.

“The Haymarket Riot,” Harper’s Weekly, May 15, 1886.

Other than on church and state issues, Kelso had not publicly spoken or written about politics since he gave some speeches during the presidential campaign of 1880. In March, 1886, he published a piece in a freethought journal protesting the exorbitant pension that Congress had awarded President Grant’s widow. The political puppets of the bondholders, bankers, and monopolists who had benefited so lavishly from the notoriously corrupt Grant administration further bled the poor toilers of the nation to pay Mrs. Grant more than $5,000 a year, he complained, while a fully disabled Civil War soldier got less than $100. The essay, though, could do little more than sputter in indignation. Its maudlin scenes—the crippled soldier unable to buy a coat; the seamstress sewing late into the night to buy a coffin for her dead child—sought to shame Mrs. Grant into repudiating her pension. When anarchism suddenly flashed into focus a few weeks later with the Haymarket bomb, it gave Kelso an ideological framework for his disillusionment with the American experiment, his outrage at the injustices of Gilded Age society, and his hopes for a better future.[2]

Thomas Nast, “Liberty is Not Anarchy” (1886), Library of Congress.

He followed the Haymarket trial closely and felt it his “duty as a man” to speak out in defense of the accused anarchists. The trial, he argued in an essay published in Chicago and Denver, tested the principles of the Declaration of Independence: a government was formed by the consent of the people, and citizens had the right to speak out against it. Citizens could even call for their government’s dissolution if they believed it had become destructive to its primary purpose, which was to secure their inalienable rights. He believed the Chicago anarchists had correctly diagnosed the fatal flaws of the United States government. The murder charge against them, he argued, had little to do with the evidence presented at the trial. “We all know that these men were really tried and condemned for being bold and able leaders of the labor movement in Chicago,--leaders whose arguments could not be answered by their monopolistic enemies, and whose voices so dangerous to monopolistic despotism could be hushed only in death. They are doomed to die simply for teaching abolitionism to slaves.”[3]

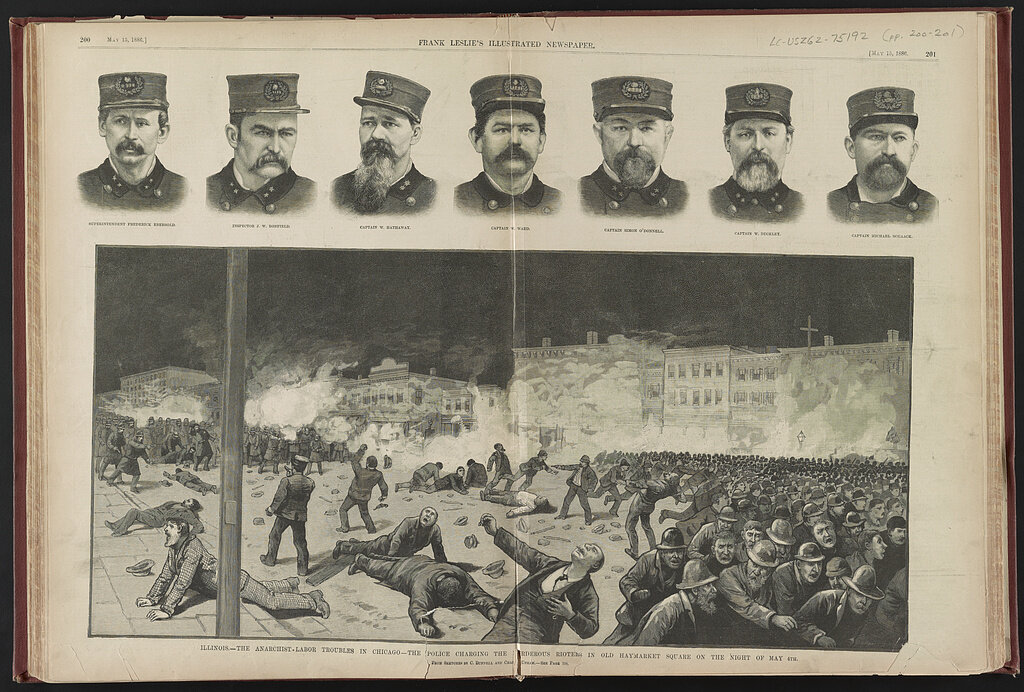

C. Bunnell and Chas. Upham, “The Anarchist-Labor Troubles in Chicago,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (May 15, 1886), Library of Congress.

Condemned to die, the Chicago anarchists would be martyrs in the coming revolution, and Kelso was ready to join them. He felt his “whole soul burning with indignation.” As the prisoners waited while their lawyers prepared an appeal to the Supreme Court of Illinois, Kelso’s allegiance to the United States hung by a thread. “I have never been an Anarchist. Hitherto, how fondly I hoped that the government which I once so dearly loved, for the salvation of which I suffered so much and fought so long and so well, might yet be redeemed from her monstrous corruptions and suffered to live for the protection of the inalienable rights of her citizens,” he wrote. “If, however, she permits this most horrible of all murders to be committed, this fond hope in my bosom will die out forever. I shall regard her redemption as impossible, her deserved doom as desirable and inevitable. And, taking my position in the foremost rank of socialistic Anarchism, I shall try to fill the place of at least one of these heroic spirits who will then have gone to the martyr’s doom, the martyr’s rest, the martyr’s glory.”[4]

Walter Crane, “Portrait of the Haymarket Martyrs” (1894).

As the condemned men waited in the spring of 1887, Kelso read A Concise History of the Great Trial of the Chicago Anarchists by Dyer D. Lum. Lum presented the Concise History merely as a compilation from the trial record, and many readers at the time and subsequently read it that way. The book, however, was in fact propaganda, masterfully paraphrasing and quoting selectively from the abstract of the trial record prepared by the defendants’ lawyers. Lum’s work would help shape the narrative of the Haymarket affair for the next 125 years. A twenty-first century analysis of the eight thousand pages in the actual trial record persuasively showed that Lum distorted the evidence to present his portrait of innocent martyrdom. The Chicago anarchists, committed to revolutionary violence on the principle of “propaganda of the deed,” had manufactured bombs matching the one that had exploded, and had conspired to attack the police in the days leading up to the May 4 rally. Kelso, however, embraced them not as bomb-throwing terrorists but as persecuted social heretics like himself.[5]

Louis Gasselin, “The Trial of the Anarchists in Chicago,” [1886], New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

On November 11, 1887, four of the Chicago anarchists—George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Albert Parsons, and August Spies—were hanged, and Kelso made good on his pledge to become an anarchist himself. In a speech before the Rocky Mountain Social League commemorating the second anniversary of the execution, Kelso’s anger was still white hot. He addressed the assembly as “Fellow Slaves.” He denounced “this absurdly so-called free country” for cruelly murdering the Chicago anarchists. “Our Martyrs” went to the gallows for “having dared to exercise their inalienable right to free speech; for having dared to expose the monstrous villainies of the mighty corporations and monopolies which, like huge anacondas, are crushing the life out of the people;-- for having dared to expose the hideous corruptions that prevail in all the departments of our government, municipal, county, state, and national.” He reviewed the scene on the street near Haymarket Square, where Pinkerton detectives and police, both tools of the capitalists, marched on a peaceful rally with a plot to destroy or at least damage leaders of the eight-hour strike. A bomb was thrown. Who threw it? Surely there had been a plan among the moneyed men to set off a bomb, blame the anarchists, and discredit the entire labor movement. The only mistake was that the hireling bomb-thrower had bad aim or a weak arm, and the explosive landed too close to the police—unless sacrificing some policemen was part of the scheme from the beginning, in order to better stoke public outrage.[6]

“Illinois: The Anarchist-Labor Troubles in Chicago” (May 3, 1886), Library of Congress.

Kelso the conspiracy theorist took easily to this interpretation of the Haymarket affair, but he was not alone: Dyler Lum had planted the idea of a capitalist conspiracy in the first paragraph of the Concise History, repeating a charge familiar in the radical press. In his speech, Kelso also denounced the trial, with its bought witnesses, biased judge, and paid-off jurors, as “the foulest blot in the history of American jurisprudence.” He described the dignified stoicism of the men on the scaffold as the assembled audience of capitalists gaped in ghoulish satisfaction. “And this, fellow slaves, is the fate held in reserve for us if we do not hurrah for our masters, and, like humble curs, lick their feet when they kick us.”[7]

Will E. Chapin, “The Law vindicated,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (Nov. 19, 1887), Library of Congress.

In the red-scare crackdown that followed Haymarket, it was dangerous to fly the flag of anarchism, though as always Kelso was a defiant moth drawn to the flame of public outrage. But what was anarchism? Kelso would explain by turning to etymology in his last book, Government Analyzed, arguing like the French theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon that “an-archism” meant not the absence of order but the absence of coercive rule.[8]

John R. Kelso and Etta Dunbar Kelso, Government Analyzed (1892).

In the red-scare crackdown that followed Haymarket, it was dangerous to fly the flag of anarchism, though as always Kelso was a defiant moth drawn to the flame of public outrage. But what was anarchism? Kelso would explain by turning to etymology in his last book, Government Analyzed, arguing like the French theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon that “an-archism” meant not the absence of order but the absence of coercive rule.[8]

In the thirteen chapters that followed, Kelso explained his new philosophy and politics ….

….

After warning that all signs pointed to a coming bloody revolution, as the people finally rose up against their oppressors, Kelso turned to his final chapter, “War.”He now believed that a state had no right to wage war except for purely defensive purposes.Murder was murder, whether done by an assassin in the night or a uniformed army flying flags and beating drums.This made him reevaluate the Civil War.The great conflict had not been a just war, he decided.The North had in fact done an injustice to the South.What right did Northerners have to compel Southerners to give up their slaves without remuneration--Northerners who themselves had profited from the slave trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and who had continued to profit from the slave economy in the nineteenth?Kelso here ignored that plans to reimburse slaveholders had in fact been discussed—as late as 1862, with Lincoln’s offer of compensated emancipation to the border states—and had been rejected by the slaveholders.[10]

John R. Kelso and Etta Dunbar Kelso, Government Analyzed (1892), frontispiece.

“But,” Kelso imagined his reader protesting, “did we not . . . preserve unbroken our great Union of States?” Yes, he answered, the carnage had saved the Union, the North’s great war aim at the outset. However, in “preserving the Union, we did ourselves an incalculable injury.” The Leviathan, the powerful nation state that emerged from the war, had all the more ability to oppress its own people. “But did we not,” Kelso had his imagined reader ask, “by means of this war, give freedom to the slaves of the south?” Kelso answered by denying that the slaves had actually been freed. “We simply changed the form of their slavery from a bad to a worse.” Antebellum slaveholders, he argued, “from motives of a pecuniary interest if not from any higher motives,” at least protected their slaves and “amply supplied all their physical wants just as they did those of their very valuable horses and cattle. In place of these protecting masters, we gave them, as masters, soulless corporations and monopolists of all kinds, who work them harder, and, in return from their labor, afford them a much poorer living than did their old individual masters, and who yield them no protection at all.” Here Kelso echoed the proslavery apologists in the antebellum South, who insisted that Southern chattel slaves were better off than the Northern wage slaves of industrial capitalism. He did not go quite so far as the postbellum Southern mythologists of the Lost Cause, who imagined happy slaves fiddling and dancing for kind Massa in Ole Dixie. Kelso did not argue that chattel slavery was good and antebellum bondspeople happy, but he did claim that the lives of blacks were even worse in the late nineteenth century, as they were “cruelly mocked” while suffering in “the utter empty shadow of liberty.”[11]

In any case, the Civil War was not really about slavery, or the Union, or constitutional rights, Kelso argued. “The war is known to have been a result of a vast conspiracy of the capitalists of Europe and of America. The object of this conspiracy was through the war, to create an immense national debt, through this debt, to obtain full control of our government, and, through this control, to reduce our entire laboring population to the most helpless forms of slavery,” he wrote. “These capitalists were the full managers of the entire arena upon which the battle between capital and liberty was to be fought. It was they who planned and carried out, to full success, the whole bloody, the whole hellish programme. By them, the question of slavery was used simply as a red flag to excite the powerful but silly bulls, North and South, to gore and lacerate each other until they were both so weakened that they could be easily brought under the yoke. Here you have it all.”[12]

Joseph Kepler, “Bosses of the Senate,” Puck (Jan. 23, 1889).

Where did this leave the Hero of the South West? Like most people, even among the enlightened, he reflected, he had not carried his emancipation from superstition far enough. “When, however, men discovered the utterly mythical nature of all the gods—the assumed source of all governmental authority—and the consequently fraudulent nature of all the governments claiming to derive their powers from these mythical monsters, they unfortunately failed to discover, at the same time, the equally mythical nature of all governments, per se, and the consequently equally fraudulent nature of all the claims to rulership founded upon the authority of these mythical monsters.” They unfortunately still believed that governments “possessed the power, by their simple commands, to make it right for their subjects to slaughter their fellowmen, to burn their villages, towns, and cities, to carry away or destroy their goods, to make slaves of their women and children and to do any and all other acts which it would be horribly cruel and criminal to do without this authority.”[13]

Kelso himself had been enchanted by the myth. “I once believed this very way myself; and when our own government called upon its ignorant and superstitious devotees to go out and butcher our brothers of the South, I promptly responded to the call,” he wrote. “I did not for a moment, think of questioning the righteousness of the required butchery. It was sanctified by the commandment of my government; and, to me, this was the commandment of my god. Believing that I was thereby fulfilling a sacred duty, and proving myself a good, brave and patriotic man, I cheerfully bore, for more than three years, every conceivable hardship and privation; took part in nearly a hundred bloody engagements; [and] with my own hands, slew a goodly number of brave men.” After the war, “I looked back with exultation upon the part I had enacted in their achievement; and viewed with pride my own once well-formed and iron-like frame riddled and broken with many wounds. How blind I was, and yet how honest. How blindly, how piously, how patriotically inhuman even the best of us are capable of being made by superstition, whether with regard to those mythical monsters, called gods, or those equally mythical monsters called governments.”[14]

………………………….

[1] On the Haymarket affair, see esp. Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), and Messer-Kruse, The Haymarket Conspiracy: Transatlantic Anarchist Networks (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2012); see also Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984) and Bruce C. Nelson, Beyond the Martyrs: A Social History of Chicago’s Anarchists. 1870-1900 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1988).

[2] D mss 14: 27; John R. Kelso, “Our Great Non-needy and Non-Deserving U.S. Paupers,” in “Miscellaneous Writings,” 301-406, dated March 16, 1886, pub. in Truth Seeker (April 17, 1886), 242-3.

[3] Kelso, “The Anarchists,” 331, 346.

[4] Kelso, “The Anarchists,” 358-9.

[5] Dyer D. Lum, A Concise History of the Great trial of the Chicago Anarchists in 1886 (Chicago: Socialistic Pub. Co., [1887]), 174. On Lum see Reichert, Partisans of Freedom, 236-44, and esp. Frank H. Brooks, “Anarchism, Revolution, and Labor in the Thought of Dyer D. Lum: ‘Events are the True Schoolmasters,” PhD diss., Cornell University, 1988, and Frank H. Brooks, “Ideology, Strategy, and Organization: Dyer Lum and the American Anarchist Movement,” Labor History, 34, 1 (winter, 1993): 57-83. On Lum’s Concise History as propaganda and William Dean Howells’ reaction, see Messer-Kruse, Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists, 153-5. Kelso also read Gen. Matthew M. Trumbull’s two pamphlets, Was It a Fair Trial? (Chicago? 1887) and The Trial of the Judgment (Chicago: Health and Home Pub. Co., 1888). Trumbull was a close friend of Samuel Fielden, one of the defendants. For the revisionist narrative of the Haymarket affair, see Messer-Kruse, Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists and Haymarket Conspiracy; the previous standard work was Avrich, Haymarket Tragedy.

[6] John R. Kelso, “Our Martyrs,” delivered before the Rocky Mountain Social League at Denver, Colorado, Nov. 10th 1889, in “Miscellaneous Writings,” 459-91, esp. 459, 471.

[7] Kelso, “Our Martyrs,” 469, 465; Lum, Concise History, [ii].

[8] On Proudhon see Benjamin Tucker, “State Socialism and Anarchism: How Far They Agree, and Where They Differ,” in Frank H. Brooks, ed., The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881-1908) (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1994), 86, orig. in Liberty (March 10, 1888); Kelso, Government Analyzed, 14-15; Tucker in Brooks, “Anarchism, Revolution, and Labor,” 173. Kelso frequently argued with recourse to etymology, so he had not necessarily read Proudhon. On anarchism generally see April Carter, The Political Theory of Anarchism (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1971). On American Anarchist thought in the 1880s see esp. Reichert, Partisans of Freedom; Nelson, Beyond the Martyrs chap. 7; Brooks, “Anarchism, Revolution, and Labor”; see also David DeLeon, The American as Anarchist: Reflections on Indigenous Radicalism (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978).

[9] Kelso, Government Analyzed, 4, 40, 106, 6.

[10] On border state slaveholders’ rejection of Lincoln’s offer of compensated emancipation in 1862, see McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 498-99, 502-4.

[11] Kelso, Government Analyzed, 297-8.

[12] Kelso, Government Analyzed, 299.

[13] Kelso, Government Analyzed, 47-9.

[14] Kelso, Government Analyzed, 47-9

![Haymarket Square, Chicago [c. 1893], Library of Congress.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fd8c8378794286b0a2c3cee/1619906886781-09UOHMZZA5S5TOZK6L3F/Haymarket+1893%2C+LoC.jpg)

![Louis Gasselin, “The Trial of the Anarchists in Chicago,” [1886], New York Public Library Digital Gallery.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fd8c8378794286b0a2c3cee/1619907641595-52UDX4JS4P6XR5F779GK/The_trial_of_the_anarchists_in_Chicago.jpg)