Kelso and the Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson

Thomas Nast, [Pres. Andrew Johnson and the Constitution], Harpers’ Weekly, March 21, 1868, Library of Congress.

[Adapted from Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy: The Civil Wars of John R. Kelso (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 285-93]:

Kelso’s 39th [Congress] would hold its second session from December 3, 1866, to March 3, 1867. A few days after Radicals held a late November torchlight procession and political rally in Springfield[, Missouri], Kelso headed for Washington.

Missouri’s radical press urged the Republican-dominated Congress to act on the mandate they had received at the ballot box. The Republicans had been timid in the last session, the Democrat wrote, but now they had the thunder of local majorities behind them. Moreover, events through the second half of 1866 had shown the folly of trying to cooperate and compromise with obstructionists. The Southern states (except Tennessee), with President Johnson’s blessing, had rejected the 14th Amendment. Former Confederates also showed their utter opposition to building a new South by striking out violently against Blacks. Whites rioted for three days in May in Memphis, killing nearly fifty Blacks and burning their houses, churches, and schools to the ground. In New Orleans in July, the violence was as bad and the political implications even worse. After President Johnson had telegraphed local authorities, urging them to break up a political meeting of Black and White loyalists, a police force manned mostly by ex-Confederates complied, leading a White mob that killed nearly 40 and wounded nearly 150. In August, Johnson then undertook an unprecedented speaking tour aimed at the election, a “Swing around the Circle” from Washington to Chicago and back. At political rallies, he lashed out at Congress and demonized his political opponents. At one stop, when a heckler urged him to “hang Jeff Davis,” Johnson shot back, “Why not hang Thad Stevens?” Radicals, he charged, promoted tyranny, treason, and disunion, while he, the Union’s much-maligned leader, was doing God’s work preserving liberty. His belligerent, undignified harangues alienated moderates and contributed to the shellacking of his supporters in the midterms. Radicals had begun talking about more aggressive Reconstruction policies and even openly considering impeachment even before all the votes were counted.1

. . .

Pres. Andrew Johnson, Library of Congress.

Had Andrew Johnson been a better politician, he might have exploited economic policy differences among the Republicans. Instead, his belligerent obstructionism repeatedly united them. Some radicals, like Thaddeus Stevens, had been long convinced that Reconstruction would never succeed with Johnson in the White House. The president of the United States was supposed to execute the laws passed by Congress. Johnson, they complained, had done the opposite. In actively thwarting the expressed will of the legislature, whose mandate was strengthened by the election of 1866, he had abused his power as commander-in-chief of the military, perverted the authority of his office, and even questioned the legitimacy of Congress itself. There had been whispers about impeachment as early as the fall of 1865. In the spring of 1866, radicals outside of Congress, in meeting halls and in the press, began to push the case for Johnson’s removal. As the election campaign heated up in the summer and fall, some congressional candidates—particularly Benjamin Butler in Massachusetts and James M. Ashley in Ohio—began calling for Johnson’s impeachment in their stump speeches. Ashley was widely reported to have vowed to “give neither sleep to his eyes nor slumber to his eyelids” (a reference to Psalms 132:4) until articles of impeachment were brought against Johnson.2

Other Republicans, however, even other radicals, saw impeachment as legally dubious, politically reckless, and ultimately dangerous for the country. . . Moreover, with the economy so fragile, and currency speculators on Wall Street betting on or against every move in Washington, a constitutional crisis might produce economic chaos.3

. . . .

Word went out [that Ashley intended to bring the topic of impeachment to the House floor], and the press reported the Ohioan’s intentions. On Monday, January 7, the galleries were full, and reporters noted a sense of anticipation and excitement in the air. But then something happened that no one expected. Missouri Congressman Benjamin Loan, with Kelso’s help, became the first representative to call for the impeachment of Andrew Johnson.4

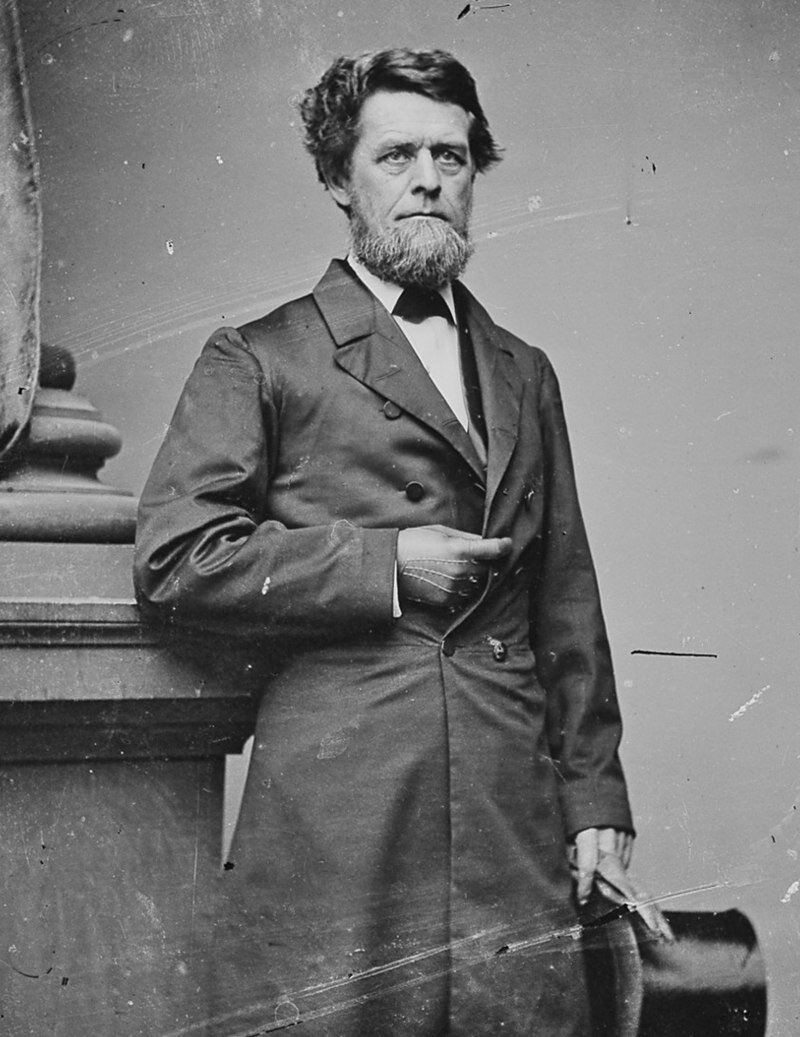

Benjamin Loan, National Archives.

Every Monday, what was called the “morning hour”—actually noon to 1:00 p.m.—was reserved for a call from the states for bills and resolutions to be disposed of without debate. On this day, when Missouri’s turn came, Loan, from the state’s Seventh District, read a resolution with a preamble and four parts. In order to secure “the fruits of the victories” gained in the war and to effect the will of the people expressed at the last election, Loan declared, it was the “imperative duty” of Congress, without delay, to accomplish four objectives. First, impeach the president, convict him “of the crimes and high misdemeanors of which he is manifestly and notoriously guilty,” and remove him from office. Second, ensure that the presidency operates “within the limits prescribed by law.” Third, reorganize the former Confederate states “upon a basis of loyalty and justice” and restore their practical relations to the Union. Finally, to achieve this last end, secure “by the direct intervention of Federal authority” the voting rights of all “loyal citizens” in those states, “without regard to color.”5

What was going on? The correspondents in the press gallery, darting from their seats to the telegraph operator, were confused; the stenographic congressional record of parliamentary moves and motions veils motives and consequences; later historical accounts hurry past these initial steps to the impeachment process itself. Loan had clearly not coordinated with Ashley: the latter immediately sprang to his feet to try to offer an amendment. . . . [But] Loan pressed forward.6

Was Loan trying to steal Ashley’s thunder and push a hyper-partisan agenda? That is what some hostile commentators in the press would charge. The New York Tribune called Loan’s “manifesto” an “incoherent and amusing resolution” by a man who was “evidently a morbid person, with the weakness of getting into print, or in some way of attracting attention.” The New York Herald would come to see him as “a radical politician, with more ambition than brains” trying to create “a sensation.” The Baltimore Sun looked beyond Loan himself to the cabal of extremist Republicans trying to drive the entire party—and thus the entire Congress, and the entire country—toward radical Reconstruction. Loan’s resolution, the Sun editorialized, “set forth the considerations of partisan expediency which require the impeachment of the president.” The resolution “precisely” expressed the position of House leader Thaddeus Stevens: “that the impeachment of Mr. Johnson is essential to the consummation of the congressional scheme of reconstruction, which otherwise is a failure.” The paper was wrong to dismiss the resolution as mere partisanship, but right to see that Loan—and Stevens, and, apparently, Kelso—were trying to make the case that reconstructing the presidency had to be part of rebuilding the republic.7

Loan’s resolution did not order specific articles of impeachment against Johnson, but it broadly declared the president to be “manifestly and notoriously guilty” of “crimes and high misdemeanors.” . . . He wanted to force the impeachment issue to the floor, not have it limited by the [Republican] caucus or stuck in a committee.8

Thaddeus Stevens, Library of Congress.

Then Ralph Hill, a moderate Republican from Indiana, raised a point of order. Since the resolution’s third and fourth clauses were about representation in the former Confederate states, they were specifically about Reconstruction. And Congress had the year before made a rule that all Reconstruction bills and resolutions would be sent immediately to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. When the chair agreed, Loan knew that his impeachment resolution was in trouble. If his radical resolution was sent to that committee, it would never again see the light of day. So Loan quickly asked the Chair if he could drop the third and fourth clauses (about Reconstruction) and just keep the first two (about the presidency). No, the Chair answered, it was too late—the resolution could not be altered after a point of order had been raised. Upon the Chair’s ruling, the resolution was sent to the Joint Committee, “amid a murmur of approval on the Democratic side of the House.”9

Just after the impeachment resolution died, Kelso resurrected it. Seated behind Loan at the back of the hall, Kelso had obviously been aware of what his Missouri colleague was doing, if not collaborating with him from the start. The Missouri delegation still had the floor for the Monday “morning hour” call for resolutions from the states. “On the instant,” according to a reporter who watched the scene, Kelso took a copy of Loan’s resolution, crossed out the third and fourth clauses, and rose to be recognized. He then reintroduced the resolution to impeach Andrew Johnson.10

Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy Figure 12.1: John R. Kelso, c. 1865-7. Portrait of US Representative John R. Kelso, Springfield, Missouri, Charles Lanham Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia. Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Kelso, like Loan, Stevens, and some other aggressive radicals, wanted a vote on the floor so congressmen would have to take a stand on impeachment before the country. . . . [A] motion to table (and thus kill) the resolution came to a vote and was defeated, 40–104—a test vote that one report described as “ominous.” Loan’s—and now Kelso’s—impeachment resolution would carry over into the next week.11

Reporters in the gallery thought the excitement was over for the day. Yet as soon as the morning hour expired, Ashley arose and interrupted the resumption of regular business with a “high question of personal privilege,” which, by rule, took precedence over everything else. Ashley charged Andrew Johnson with “high crimes and misdemeanors,” specifying that the president had illegally usurped power and corruptly pardoned rebels, appointed officials, vetoed legislation, and disposed of public property. The resolution would authorize the Judiciary Committee to investigate with subpoena power, and then, if appropriate, report articles of impeachment back to the House. As Ashley spoke, according to a correspondent, “members came from the lobbies down the aisle to their seats; the galleries became more compact than ever; the gold speculators vibrated rapidly between the reporters’ gallery and the telegraph in its rear; all present were full of excitement and anxiety.”12

Ashley called the question. Opponents moved to table but were defeated in a vote almost identical to the tabling motion on Kelso’s: 39–105. Then they tried to get Ashley’s resolution referred to the Judiciary Committee before a vote could be taken to authorize the investigation, but they failed again. Finally, the House voted on the impeachment investigation resolution itself, and it passed, 107–39.13

Ashley would become known as the “Great Impeacher.” In the radical Missouri press, Loan got some credit, too, for being the first to bring the issue to the House floor. A headline in an Ohio paper summarized the day’s events: “Impeachment. Exciting Scene in the House. Two Impeachment Resolutions. Messrs. Loan and Ashley the Movers. The Latter’s Measure Passed.” Kelso, who kept the impeachment issue alive on the floor and forced the first test vote, was barely mentioned in some accounts and completely absent in others. One newspaper report misidentified him as “Mr. Kelley,” a Republican from Pennsylvania. Another called him “Retzer.”14

A week later in the House, Benjamin Loan hurled an even more explosive accusation against the president: he charged Johnson with having been complicit in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. . . . On Monday, January 14, Kelso opened debate by withdrawing his demand for the previous question and yielded ten minutes of his allotted hour to his colleague. Loan had not gotten far into his speech before he made the charge. We have learned, Loan began, that Lincoln’s death was not the desperate act of a lone gunman but the result of a rebel conspiracy. Defeated on the battlefield, rebel leaders had realized that the best way to further their cause was to replace Lincoln with the “life-long pro-slavery Democrat” who had, in a gesture of reconciliation, unfortunately become vice president. “The crime was committed. The way was made clear for the succession; an assassin’s bullet, wielded and directed by rebel hand and paid for by rebel gold, made Andrew Johnson President of the United States of America. The price that he was to pay for his promotion was treachery to the Republic and fidelity to the party of treason and rebellion.”15 . . . .

1 “Should Johnson Be Impeached?” [St. Louis, Mo.] Democrat (Nov. 14, 1866): 2; “Springfield, Mo.,” ibid. (Nov. 28, 1866): 1; “The Washington News,” ibid. (Dec. 5, 1866): 1; Benedict, Compromise, 202, 204–206; Foner, Reconstruction, 264–65.

2 Patrick W. Riddleberger, 1866: The Critical Year Revisited (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979), 230–49; Trefousse, Impeachment, 50.

3 “Impeachment of the President,” New York Tribune (Jan. 8, 1867): 4.

4 “The News,” New York Herald (Jan. 7, 1867): 4.

5 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 319.

6 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 319. For a garbled press account, see “Washington: Important Proceedings in Congress,” New York Herald (Jan. 8, 1867): 3. The best historical account of the Loan-Kelso impeachment resolutions as a prelude to Ashley’s (though it is just a brief synopsis) is probably Trefousse, Impeachment, 54.

7 “The Impeachment of the President,” New York Tribune (Jan. 8, 1867): 4; “The Hon. Mr. Loan’s Attack upon the President,” New York Herald (Jan. 16, 1867): 4; “The Proposition for Impeachment,” Baltimore Sun (Jan. 11, 1867): 2. The Herald article was written after Loan linked Johnson to the Lincoln assassination (see below).

8 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 319.

9 Ibid.; “Washington,” New York Tribune (Jan. 8, 1867): 1.

10 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 320; Washington,” New York Tribune (Jan. 8, 1867): 1.

11 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 320; “The President’s Impeachment—The Initial Step Taken in Congress,” New York Herald (Jan. 8, 1867): 6.

12 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 320–21; Barclay, Barclay’s Digest, 137; CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 320; “The President’s Impeachment—The Initial Step Taken in Congress,” New York Herald (Jan. 8, 1867): 6.

13 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 7, 1867, 321.

14 On Ashley as the “Great Impeacher,” see for ex. [no title], [New Haven, Conn.] Columbian Register (Feb. 9, 1867): 2; “Ashley, the Impeacher,” New Orleans Times (Aug. 14, 1867): 4; “Ashley and Forney,” New York Herald (Oct. 6, 1867): 6; “A Scheme Against Ohio,” [Macon, Ga.] Macon Weekly Telegraph (Nov. 22, 1867): 5; The Amiable Ashley,” [Concord] New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette (Dec. 11, 1867): 2. The St. Louis Democrat, in “Impeachment” (Jan. 16, 1867): 1, saluted Loan as “the first member of Congress to offer resolutions for the impeachment of the President.” “Review of the Week. The Action of Congress” (Jan. 12, 1867): 2, misidentified Kelso as Kelley; “Night Dispatches,” [Galveston, Tex.] Flake’s Bulletin (Jan. 15, 1867): 5 (“Retzer”).

15 CG, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Jan. 14, 443–44.

![Thomas Nast, [Pres. Andrew Johnson and the Constitution], Harpers’ Weekly, March 21, 1868, Library of Congress.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fd8c8378794286b0a2c3cee/1619462090542-UNAYHUV4Z34TM9FPWL12/image1-31.jpg)